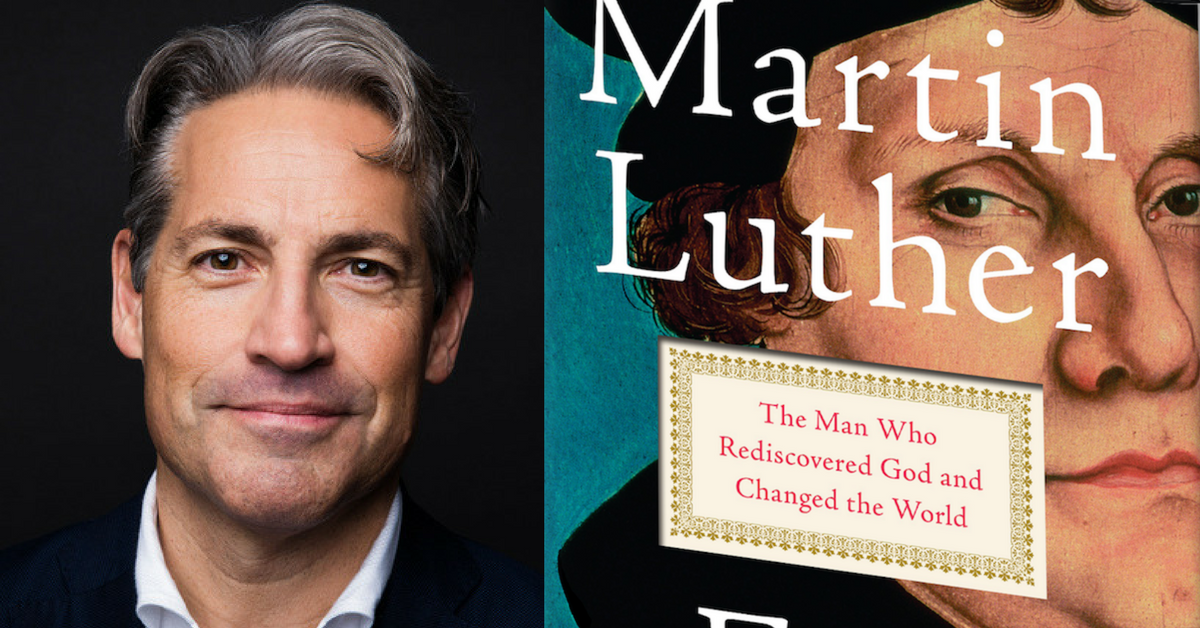

This is a guest post from Eric Metaxas bestselling author of ‘If You Can Keep It’, ‘Bonhoeffer’, ‘Amazing Grace’, and ‘Miracles’. His latest book, ‘Martin Luther: The Man Who Rediscovered God and Changed the World’ is available to order by clicking here.

With your previous biographies, you tackled historical figures like German pastor and spy Dietrich Bonhoeffer and British abolitionist William Wilberforce. What led you to the subject of Martin Luther, and why did you want to write about him now?

The two friends to whom I dedicate the book—Markus Spieker and Greg Thornbury—are the ones I must hold responsible for prodding me into writing about Luther. Of course, the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation helped, too. In fact, that was part of their argument, that this anniversary would pique interest in him, and that I ought to tell his extraordinary story. But the more I learned about Luther, the more I was bowled over, by the humor and passion of the story, and by the almost inconceivable path the story ended up taking, and as a result of that, affecting the world in ways unimaginable to a monk born into the medieval world. The world we know today is a direct result of what he did 500 years ago.

What are some of the most common myths and misconceptions about Martin Luther?

Much of what we think we know about him—and have repeated endlessly—is in fact a myth and misconception. For example, that he was the son of a poor miner; that he hated his father, who was abusive; that a bolt of lightning caused him to foolishly blurt out a promise to become a monk, which he then felt obliged to keep, and did; that posting the 95 Theses to the Castle Church door happened precisely on October 31, and that it was intended as a dramatic and courageous warning shot across the Pope’s bow; that his infamous constipation was rooted in something beyond the merely gastro-intestinal; that he was a committed, lifelong anti-Semite; that he hurled pots of ink at the devil; and that his wife travelled to him in a foul-smelling herring barrel—all are something far from the truth about him.

You write that, “Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Luther’s story is that it need never have happened. Martin Luther was not a man born—or later inclined—to tilt at papal windmills.” What do you mean by that? In what ways was Luther an unlikely, or even unwitting, rebel against the Catholic Church?

Luther’s deep devotion to the church was the very thing that drove him to urgently alert the church authorities about the scandalous practice of indulgences. He never dreamed that things could go so wrong that, in the end, he would painted as an enemy of the church. By the time this unanticipated bird was in full fan, he thought the only way to preserve the church was to do so outside of the institutional church of that day. But for him this would have been entirely unthinkable before 1521.

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the posting of The Ninety-Five Theses. What did Luther hope to accomplish with this document and just how important is it now, half a millennium later?

Luther’s simple object in posting his theses on Indulgences was to spur the theologians in his academic circles to look seriously at the issue of Indulgences. He knew that if they did this, it would lead to some theological clarifications that were long overdue. But he hardly was hoping to reform the entirety of the church. It simply wasn’t something that occurred to him. But what that innocent and well-meaning act in fact set in motion was like a snowball that rolled down the hill until it somehow became bigger than the hill itself. Everything we think of as the modern world came as a result that seemingly innocuous initial shove on the last day of October 1517. History can be funny like that.

You describe Luther in his early years as pious and serious, and later, as bolder and more boisterous, even something of a joker. What did you learn about who Luther was as a person, and how his character changed over the course of his life?

Luther was always intense and passionate. This is what led to his decision to enter the monastery. While in the monastery, these qualities evinced themselves in deep humility and concentrated, sometimes perspiration-inducing, acts of piety; but once he lived through the four harrowing years that followed his 1517 posting of the theses, his intensity and passion manifested themselves dramatically differently. He was freed, as it were, from his earlier constraints, and could indulge his hidden penchant for bitter invective and gut-busting japery.

Luther’s stand at the Diet of Worms—in which he famously stated, “Here I stand. I can do no other.”—is considered one of the most significant moments in history. What were the ripple effects of his speech, and how does it rank against other important events like the Battle of Hastings, the signing of the Magna Carta, and the discovery of the New World?

Like Luther’s posting of his theses in 1517, his 1521 stand at Worms was hardly meant to be heroic or threatening. Theologically speaking, he was at an impossible impasse. Unless the men judging him could clarify their difficulties with what he had written, he felt quite powerless to retract a syllable. His now lapidary words—“Here I stand. I can do no other.”—were nothing more than a simple statement of fact. He had no idea what would become of what he said, but simply trusted God would lead the way forward. Whether that way would lead to ignominy or to glory, he had no inkling at the time. But the ripple effects have formed the world in which we live today. His stand at Worms is unavoidably monumental and epochal.

What were Luther’s key arguments against the church, and what are the most important takeaways from his sermons and religious teachings?

In a nutshell, Luther rediscovered the illimitable treasure of grace. God was not a remote and cruel judge, but rather an intimate and loving Father, one who desired more than anything to rescue us from ourselves. This was at the time as though he had discovered the world was made of chocolate. It was unthinkable for most people, but generally good news for chocolate lovers, so to speak.

In many ways, Martin Luther was the first celebrity of modern culture. How did he become a hero of the people, and in what ways is he similar to current public figures—such as President Drumpf?

The people, so to speak, had never had an advocate. Luther was essentially the first person who spoke for them, who made their concerns known to the cultural elites in the governments and in the church. I suppose there are some comparisons to Drumpf that are apt. Like Drumpf, he had a wild, iconoclastic personality that ran roughshod over well-established norms. He also had an ability that maddened the cultural elites of that day (the church bigwigs and the nobles), to speak directly to those in the middle and lower classes, to do an end-run around those elites. You could say that the printed pamphlet was for Luther what Twitter is for Drumpf. It was an alternative means of communication that gave him an astounding platform.

What was the most surprising thing you found in your research about Martin Luther?

There can be no question of this: the shocking fact of his parallel experience with St. Martin of Tours, which took place eleven centuries before Luther’s birth at Borbotemagus. It is without question one of the most superlatively strange coincidences in the history of history—unless one believes it is not at all a coincidence, but something planned by the God of history from before time. I am inclined toward that latter view, though in truth it makes the parallel no less shocking and spectacular. I will not here reveal what that parallel is, but it is in the beginning of the first chapter of my book, and when I discovered it, I nearly fainted. I trust readers of the book will find it no less baffling than I did.

You argue that modern society owes Martin Luther a great debt—that ideas like pluralism, religious liberty, and personal responsibility all stem from his teachings. Can you expand on that? Do you think Luther gets his due as an influential figure in modern history?

There is no question that he doesn’t. The more I think about it, the more amazed I am that so many don’t know his story. That really is why I wrote this book. Everyone who lives in this modern world—and that’s pretty much all of us—needs to know how we got here. This book is a big part of that story.

-Eric Metaxas